Cuba's digital destination

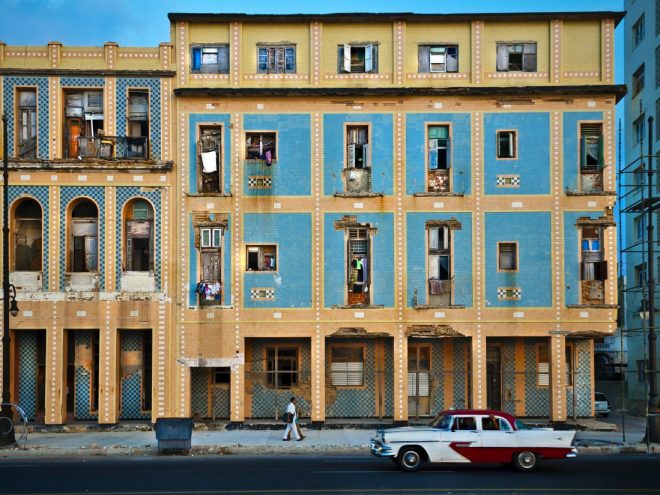

An architectural stew

by Victoria Alcalá

Havana has always been a very cosmopolitan city, open to different influences. As a port city, it is constantly used to the comings and goings of fleets, of receiving people from every continent, some in transit and others arriving as conquerors or refugees from wars and conflicts; a few of these people succumb to the city’s charms and end up as “adopted” habaneros.

The Spanish and African peoples have left the most visible marks, but Chinese, Arabs, Jews, French, Belgians, Americans, Russians…all have left their imprint on the spirituality, tastes and idiosyncrasies of the city’s inhabitants.

Since spiritual heritage is extremely difficult to pinpoint and one could fall into the customary common perceptions of vociferous Africans, homesick Spaniards or pragmatic Yanks, I would instead like to talk about the solidity of stone, the tangible testimony of architecture, in order to show my city as a portion of that “ajiaco,” or stew, which, for Cuban ethnologist Don Fernando Ortiz, is the “Cuban essence” and in this case particularly, the “Havana essence.”

That’s why it is better to leave behind the colonial era when the Spanish presence, rather than being assimilated, was imposed by blood and fire and whose architectural monuments, many of which are admirably preserved, are very well known.

The twentieth century opened with the presence of the interventionist US Army, the dismantling of the Spanish colonial apparatus and the installation of the Republic. But the Spanish dominion having ceased over the Island did not mean that the Spaniards or their legacy disappeared. It will never be known exactly how many of them remained in Cuba with their families, customs and preferences while others arrived in the first years of the Republic with their dreams of making a fortune (and of escaping military service in Spain). And so the imprint of the Iberian Peninsula on Havana architecture would continue well into the century.

There was an element that made a perfect link with the eclecticism being imposed: the Mudéjar style. This in turn was Hispanic-Arabic syncretism seen all over Spain for eight hundred years and very evident in our first colonial buildings. The Cuban Creole Neo-Mudéjar is very evident, for example, in the Sevilla Hotel (Trocadero St. on the corner of Zulueta St.; 1908; engineers José Toraya and Aurelio Sandoval), whose façade and interiors celebrate a connection with Granada’s Alhambra; in the Palacio de las Ursulinas (Egido and Sol streets, 1913, attributed to Toraya) and in its neighbor the Universal Cinema (1942); and lavishly visible in the splendid “castle” of the La Tropical Gardens (1912), whose interiors also make reference to the Alhambra. The use of Moorish arches in multiple and often surprising combinations, and tiles from Seville trimming the baseboards, façades and interiors was relatively commonplace.

The explosion of modernism or Art Nouveau in the Island is also very much connected to Spain, to such a degree that it was sometimes referred to as “Catalan style.” Perhaps it was used in a pejorative sense because it departed so drastically from Academic canons, but it is well-known that since the nineteenth century, Catalans had been very active in building in the Capital. The name of Mario Rotllant from Barcelona stands out: he was the proprietor of the cement company bearing his name, dedicated not just to building but also to producing cement and plaster decorations for interiors. Rotllant was in charge of several of the best examples of Art Nouveau in Cuba, such as the stylistically unified group of homes on Cárdenas St. with their curvilinear forms, delicate grille-work and voluptuous plant forms, as well as other remarkable examples like the residence of Dámaso Gutiérrez in the neighborhood of Víbora (Patrocinio 103, between Saco and Heredia) and the Masía L’Ampurdá in Sevillano (Gertrudis St. on the corner of Revolución St). Later, something we could call “neo-Gaudinism” would permeate a number of avant-garde Cuban buildings. We can recognize it in the parabolic arches of the Tropicana Nightclub, just to mention one example. When in the 1960s the multiform structures of the National Arts School was built, architects used the tested economy and efficacy of Catalan vaults.

But it was not just the Catalans who made use of these influences: Cuban architect Eugenio Dediot designed the building known as El Cetro de Oro (301 Reina St., between Campanario and Manrique, Centro Habana; ca. 1905) for a business that took up its ground floor. Today, despite its sad state of deterioration, we can still admire a profusion of delicate Art Nouveau resources. The Crusellas House, also on Reina, St., remodeled by Cuban architect Alberto de Castro, pulled together some attractive Art Nouveau elements in the original structure. The La Tropical Gardens (1904), at the beer and malt beverage factory belonging to the Blanco Herrera family originally from Catalonia, were supervised by Ramón Magriñá and they provide yet another demonstration of how Art Nouveau sensuality was inserted into the Creole milieu.

Havana residents were partial to the exotic delights of Chinese porcelain, but there are few visible examples around of the Chinese presence in architecture. Nonetheless, the large Chinese community in the city managed to superimpose some of their identifying traits when they put up buildings in Chinatown, surprise us with Chinese features in places so far from downtown Havana as Párraga, and especially in the Chinese Cemetery (26th St. on the corner of Zapata Ave., Nuevo Vedado; ca. 1893; architect Isidro A. Rivas).

The very closed circle of the Jewish community has hardly left any physical traces of their presence in Havana. Nevertheless, the Patronage of the Jewish Community (13th St. on the corner of I St., El Vedado; 1953; architect Aquiles Capablanca) intelligently chose the dynamism of the modern architectural movement combined with a detailed study of Hebrew traditions and the ideas being used to build synagogues at the time in the US to build their own Beth Shalom Synagogue. From a distance, it can be recognized by its giant reinforced concrete arch symbolizing the rainbow that announced the end of the Great Flood. These days the former Patronahe functions as the Bertolt Brecht Cultural Center, but the synagogue remains open for its congregation on the weekends.

It is quite another picture when we examine the US influence on domestic, civil and even religious architecture. The imposing and inevitable National Capitol Building (the city block bordered by Prado, San José, Industria and Dragones streets, Centro Habana; 1929) was initially a project directed by architects Eugenio Rayneri Sorrentino and his son Eugenio Rayneri Piedra, but underwent numerous changes at various times under Félix Cabarrocas, Evelio Govantes, Raúl Otero and José M. Bens Arrarte. Built by the firm of Purdy and Henderson, it is one of those cases showing the preference for imitating “classical” styles as a demonstration of family or company power, magnified here by the fact that it was the representation of the government itself since the building housed the Senate and the House of Representatives. In its opulent interiors overloaded with bronze, Carrara marble and hardwoods, the Hall of Lost Steps (Salón de los Pasos Perdidos) amazes us with its monumental Statue of The Republic. On the exterior, the massive entrance staircase, the giant statues flanking the entrance, the dome (one meter higher than the dome of the Washington Capitol, as Cubans are fond of boasting) and the landscaping by Forestier provide the city with a magnificent landmark. Currently under major restoration, it is planned to become the home of the National Assembly of the People’s Power.

Obviously the first Cuban skyscrapers were influenced by the North, just like bank buildings. A typical example is the Banco Nacional (Obispo and Cuba streets, Old Havana; 1907 and 1919; architect José Toraya), commissioned to (wonder of wonders!) the firm of Purdy and Henderson, who were in charge of designing a steel-frame building with foundations, roofs and floors of reinforced concrete, brick paneling and a marble facade decorated with carved stone. It had a Corinthian colonnaded portico that held up the giant pediment. Inside, the rooms were organized around a central courtyard, which, after the second floor, had no roof, and it made lavish use of marble, bronze and hardwoods. Today it is the headquarters of the Ministry of Finance.

Neither religious architecture (which up to the beginning of the century was practically the sole domain of the Catholic Church) nor domestic architecture was unable to escape the influence of the United States. And so we saw the proliferation of a number of Protestant churches, California bungalows, homes and buildings inspired by Art Deco or the Modernist Movement as it appeared in the United States. Perhaps the most outstanding example would be the house of the Swiss banker Alfred Schulthess (19 A St. between 150 and 190 streets, Cubanacán; 1958; architect Richard Neutra, in collaboration with Cuban architects Raúl Álvarez and Enrique Gutiérrez). This was the only work in Cuba by the famous Austrian-born US architect Richard Neutra, who has a long list of celebrated houses, like the Kaufmann Dessert House, just to name one example. The compositional clarity, transparence and elegant sobriety of the design were complemented by the gardens by Brazilian landscape architect Roberto Burle Marx. These days the house is used as residence for the Swiss Ambassador in Cuba. The American influence is also substantial in hotel architecture as in the cases of the Nacional, Riviera and Habana Libre hotels (the latter, the ex-Havana Hilton Hotel).

Furthermore, there is also a sometimes diffused European presence, with unexpected examples, like the Reformed Presbyterian Church (214-222 Salud St. between Lealtad and Campanario streets, Centro Habana; 1906 ―or 1907; architect Benjamin de la Vega ?), a project imported from the US but carrying a strong Scottish neo-Gothic influence that can be appreciated, for instance, in its striking campanile crowned by a weather vane with the shape of a rooster. Thanks to an interesting article by essayist Gina Picard, I learned a few facts about a house I had often noticed in Santos Suárez, at 109 Heredia St. between Estrada Palma and Luis Estévez streets, which was built in 1909 in a rather unusual European style. Picard tells us that there are two versions about its filiation. According to its present owners, it was built by a Jewish family whose son had studied in Holland and he conceived the design as something representing typical Dutch architecture. But this same house appears catalogued within the Arts and Crafts movement in the Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Art. Cuba Theme Issue (Japan, Wolsson Foundation, No. 22, 1996). When we recall that the Arts and Crafts Movement preceded Art Nouveau, then this is rather a rare example we have sitting on a street in Santos Suárez.

Perhaps even more mysterious than the little house on Heredia St. is the small “castle” in the Lawton neighborhood of 10 de Octubre district. With its stone walls and red pitched roof, it looks like it materialized from some remote French or German town. I have not been able to dig up any information about it. At some point it was a restaurant, but I do not know its function today. Another building that escapes the traditional eclectic codes of the era is the modest Tudor style building which houses the Manuel Saumell Elementary School of Music (660 F St., El Vedado; 1925). When we look at the Alberto de Armas house (9, 2nd St., Miramar; 1926; architect Jorge Luis Echarte) we are treading on somewhat firmer ground: larger and more imposing than the previous examples we have cited, known popularly as the House of the Green-Tiled Roof (Casa de las Tejas Verdes), its steep pitched roof, tower and spire, and dormer windows immediately draw our attention to it as we exit the tunnel connecting El Vedado and Miramar.

From the mid-1960s, the El Conejito Restaurant (M St. on the corner of 17th St., El Vedado; 1966; architect Gustavo Botet) brazenly refers to the traditional English world of hare hunting, both in its interior and the exterior. Finally, well into the twenty-first century, Our Lady of Kazan Holy Orthodox Cathedral went up on Avenida del Puerto in 2008. Its golden onion domes shining over the Historical Center of Havana contradict Eusebio Leal’s observation that the Soviets had not left even the name of a drink in Cuban culture. A tiny piece of Moscow inserted into the Cuban capital is just the dollop of sour cream missing in our Havana stew.