Cuba's digital destination

Cuba Beyond the Beach: Stories of Life in Havana

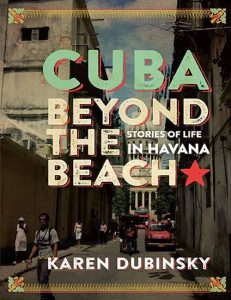

The new book “Cuba Beyond the Beach: Stories of Life in Havana” from one of Canada’s best Indie presses takes readers beyond the beach and deep into Cuba’s soul. Karen Dubinsky’s refreshing prose introduces readers to Cuba’s complex, fascinating capital city by sharing stories of life in Havana from her unique perspective as a teacher, researcher, and friend who visited Cuba for the first time in 1978 and has visited regularly (2-3 times a year!) since 2004. The book is more than a travelogue and more than a memoir. It’s a window into neighborhood life in Havana, how Cuban artists, intellectuals, and just plain old regular people adjust to life in the new economy and the complexity of the ties that form as the world comes to Cuba, and as Cubans move out into the world. The stories shared in the book not only feel like Cuba but the author succeeds in capturing the stories behind the sounds of Cuba. This intimate portrait of life in Havana, vibrates with the sounds of the city: jazz, rock, hip hop, fusion (and yes, even reaggaeton.) As the author writes in one section dedicated to Cuban music, “The whole country is a playlist.”

“Those Who Dream With Their Ears: The Sound of Havana”

“Those Who Dream With Their Ears: The Sound of Havana”

A Selection from Cuba Beyond the Beach: Stories of Life in Havana

By Karen Dubinsky

One of my first experiences of the sound of Havana occurred in a moment, as I was walking one evening in Vedado near the beautiful old theatre Amadeo Roldán. A young man stepped out of his house just as I was passing. He put a trumpet to his lips and began playing, simply and beautifully, as I walked past. It was night, not very late, and the music followed me as I continued walking down calle Calzada toward my apartment.

A random, lone trumpet sounding melodically in the city night sky, it’s almost a clichéd Hollywood image, but it happens from time to time in Havana. If you can’t wait for a random moment, take a walk along avenida Boyeros, near the Omnibus Terminal, not far from Revolution Square. Across the street is a stadium where, owing to the great acoustics provided by the cement awnings, horn players regularly gather to practice. The same thing happens on the Malecón, near the statue of Antonio Maceo, where an underpass (which is always closed) also attracts horn players. Geographers claim that music is how Havana neighbourhoods are transformed from “space to place” – traditional son is the sound of tourist-heavy Old Havana, drums are persistent in predominantly Afro Cuban Centro, and internationally inflected jazz reigns in cosmopolitan Vedado.[i] Personally, I hear more of a mixture than a boundary when I walk these streets, but the point is, Havana is a musical city.

The richness of Cuban music has drawn attention and visitors for over a century. “Why is Cuban music so good?” is a question I pose as research to my Canadian students, fully and ironically aware that this formulation skews the results. But that is my point: we can begin the discussion from the premise that Cuban music is “so good.” There are plenty of ways to explore why that is so, but most would agree that syncretism or cultural mixing provides part of the answer. Cuban music mixes historical and geographic influences like nothing else. In Havana one can appreciate not only the immense quality of Cuban music but also its variety. Genres such as salsa, son, bolero, mambo, and jazz are familiar to foreign audiences because of how they have crossed borders. In Havana one can hear the full range of traditional or classical Cuban sounds, as well as genres that might take visitors by surprise: trova (which is comparable to folk), hip hop, rock, reggaeton, metal, and country have all been remixed and reinterpreted in distinctly Cuban ways.

There are dozens of venues in Havana to hear some of the best music of the world. I can still hear Kevin Barreto playing the classic “Viente Años” (Twenty Years) on his trumpet at La Zorra y el Cuervo, a popular jazz club on La Rampa in Vedado. I have been deliriously happy hearing a range of different music from the undulating 1950s balconies at the Mella Theatre on calle Línea, under the stars at the beautiful outdoor club El Sauce in Playa, as well as at two other popular venues, el Brecht and the Fábrica de Arte Cubano. However, walking the street, day or night, is almost like attending an ambulatory concert—or rather a series of concerts. In Havana “garage bands” are rooftop bands or balcony bands or courtyard bands, audible at various levels all over the neighbourhood. If you live near a park or community centre you don’t need to know the schedule of musical events during the weekend, because a strong breeze and an open window (which all of them mostly are) will deliver the sound right to your apartment. One December evening during the Havana Jazz Festival I decided, after a lot of late nights in a row, I needed a night in. Reluctantly, I stayed home to catch up on some sleep. I should have known better. That night, right from my bed, I listened to one of my favourite ensemble groups, Interactivo, perform outdoors at a cultural centre two blocks from my apartment—the same beautiful set that had done me in when I had heard them play the night before in a club.

All this music-making doesn’t just happen. It is a cliché that Cuban musicians are among the best in the world, but it’s not by magic.[ii] The Cuban Revolution built a tremendous education system in the early years, and music education was no exception. Here they built on a pre-existing tradition of musicianship, handed down from generation to generation. Cuba’s long history as a tourist destination actually nurtured this musicianship, as generations of fathers taught generations of sons (and occasionally daughters) to perform old standbys like “Guantanamera” for generations of tourists. After 1959, the Cuban government expanded and formalized this training, turning golf courses into music schools and opening countless neighbourhood casas de cultura, cultural centres. The new government closed the nightclubs and casinos, and plenty of world-famous musicians such as Celia Cruz left for Miami and New York. But those who stayed saw a different kind of musical culture develop, which emphasizes performance over album sales, and provides sophisticated education even when the most basic elements like proper instruments remain scarce. Even through the Soviet years of grey, ideological rigidity, music remained defiantly Cuban, and both musicians and audiences alike are educated and selective.[iii] Cuba is one of the few places in the world where, when a child declares their intention to be a musician, parents might actually be pleased.

In November Cuba Beyond the Beach will be available online at the mainstream Amazon.com and Amazon.ca but small indie presses have to wait longer for Amazon to distribute, so, for those eager to keep reading, the best thing to do is to order directly from the publisher Between The Lines’ website at https://btlbooks.com/book/cuba-beyond-the-beach ($24.95).

[i] John Finn and Chris Luckinbeal, “Musical Cartographies: Los Ritmos de los Barrios de la Habana” in Ola Johansson and Thomas Bell, (eds.) Sound Society and the Geography of Popular Music (Surrey: Ashgate, 2009), pp. 127-144.

[i] John Finn and Chris Luckinbeal, “Musical Cartographies: Los Ritmos de los Barrios de la Habana” in Ola Johansson and Thomas Bell, (eds.) Sound Society and the Geography of Popular Music (Surrey: Ashgate, 2009), pp. 127-144.

[ii] I owe this observation to Ruth Warner, from a frustrated text exchange about the general level of ignorance concerning Cuban musical training, in December 2015.

[iii] This history of musicianship and music education in Cuba draws from

Robin D. Moore, Music and Revolution: Cultural Change in Socialist Cuba (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006).