Cuba's digital destination

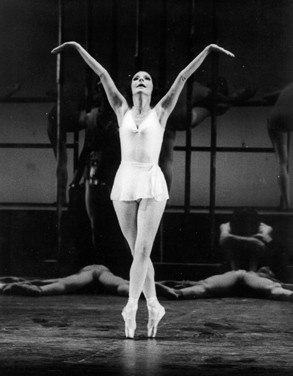

Alicia Alonso – The Grand Dame of Cuba

by Stephen Gibbs

To enter Alicia’s Alonso’s office is to visit an inner sanctum. She works in a small room, tucked away behind the unassuming headquarters of the Cuban National Ballet, on Calzada in Vedado. Outside, gaggles of young ballerinas gather. Inside, an army of efficient secretaries protect her from the uninvited.

The room itself is dark, and spartan. The shutters are drawn. There is little furnishing apart from a single bookshelf and a large mahogany desk. Behind it sits the woman who has been the face of Cuban Ballet for almost seven decades.

In the 1950s, Alicia Alonso was voted one of the most beautiful women in the world by Harpers and Queen Magazine. You don’t doubt it. Immaculately made up, her jet black hair tied back, wearing a long flowing gown, she is elegance defined. She greets me with a “good morning” in American English.

Alicia Ernestina de la Caridad del Cobre Martínez Hoya was born in Havana in 1920. Her family had no shortage of money. When it was noticed she had a talent for music and dance, she was quickly enrolled in the Sociedad Pro-Arte Musical.

At 16, she married a fellow ballet student Fernando Alonso, and the two moved to New York. In those days the move was not so unusual for well connected Cubans. She soon became one of the founding members of the American Ballet Theatre. By the late 1940’s, she was considered one of the world’s greatest dancers.

“If you wanted to be a ballet dancer back then, you had to leave the country,” she explains. But Alonso remained determined to promote ballet in Cuba, and so in 1948, in Havana, she set up the Alicia Alonso Ballet Company.

The school was largely funded by the then burgeoning Cuban high society, with wealthy patrons happy to have their names associated with such a distinguished project. The Cuban Ministry of Education also made a modest subsidy.

But by the mid fifties, the company had run into financial difficulties, and also political problems. Facing increasing domestic upheaval, President Batista attempted to recruit the Alonso Ballet Company to his cause. He wanted the group to dance on demand, often in order to distract people from nearby student protests. When the dancers refused, all funding was cut.

The school folded temporarily, and Alicia left Cuba once again, this time to join the Monte Carlo Ballet. She returned when Batista’s government was overthrown by the Cuban Revolution in 1959.

“Fidel Castro sent me a message,” she recalls. “He said, ‘What do you need to make the company the way you want it?’ So we sent him a big list of our dreams.” Within weeks, the school was receiving generous funding. It was renamed the Ballet Nacional de Cuba.

In one of the more evocative, and true, tales of the Cuban Revolution, the group then went on a tour of Cuba, demonstrating ballet to people in the most remote parts of the island. Most of the audience had never seen the dance before.

“It was beautiful,” she says. “People were amazed. But they understood what we were doing so quickly. Ballet is a natural art, the art of movement.”

Throughout her career Alicia Alonso has struggled with her eyesight. In the 1940’s she was first diagnosed with a detached retina, and she has been through several operations since. She is now nearly blind, but still actively supervises all the Cuban National Ballet’s work, and choreographs, using her loyal assistants to interpret her directions.

“I explain what I want, and show them by moving my arms and they understand perfectly well.”

Cuban ballet, while influenced by Russian and Soviet styles, is now recognized the world over as having its own unique form. Alicia Alonso says it reflects how Cubans really are. “The woman is very feminine and the man is very masculine. They dance as partners. And we move in a very light way.”

The grand dame of Cuba admits that it has been difficult to perform in a world dominated by commercial temptations. Over the years, several Cuban dancers have defected and failed to return to Cuba after tours abroad. It is not a subject she likes to discuss. “It is like growing a beautiful big tree, only to see people taking branches away,” she says. “It hurts.”

But the tree keeps re-growing. This year, the school Alicia founded will celebrate its 68th birthday.